On 25 January, Protection International’s Thailand office facilitated an event with the Thai NGO Coordinating Committee on Development (Thai NGO-COD) focused on the upcoming elections and the referendum process towards a new Constitution. We asked our country representative, Pranom Somwong, about this important democratic moment in Thailand, PI’s role in facilitating the space, and what the outcomes mean for the right to defend human rights in Thailand.

What is significant about Thailand’s upcoming general election and constitutional referendum?

On Sunday, 8 February, Thai citizens will participate in a general election and referendum. The referendum will ask whether the junta-drafted 2017 Constitution should be replaced, marking a historic opening for a Constitution shaped by the people.

Grassroots movements, including women human rights defenders, are pushing for a new constitution that centers human rights, government decentralisation, welfare, and civilian control over the military.

Which movements and organisations were represented at this event?

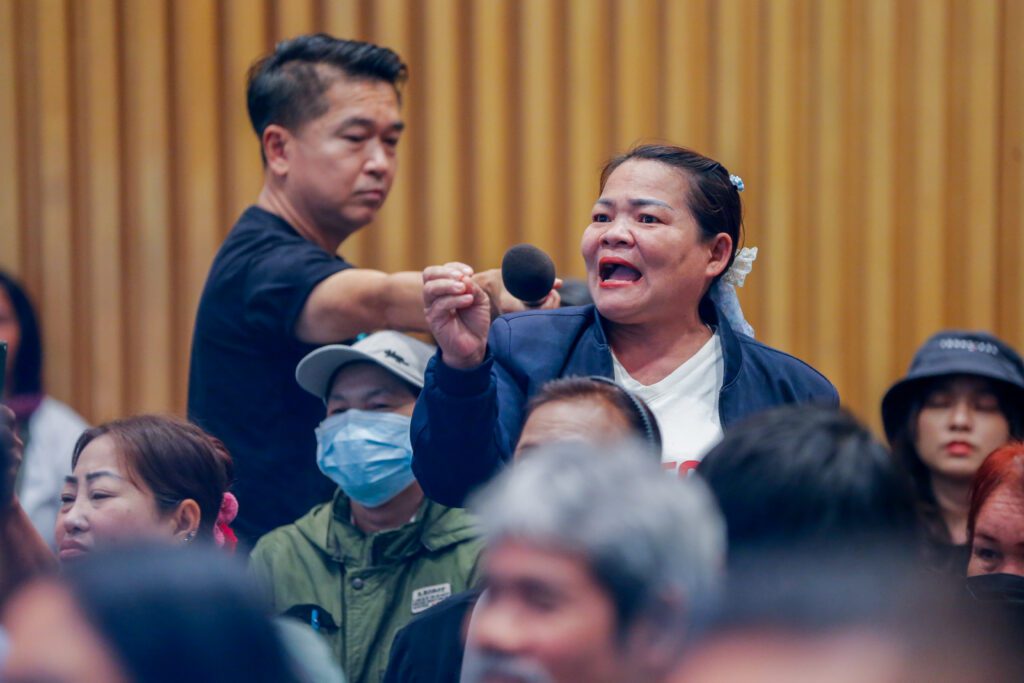

The event was organised by PI and the NGO Coordination Committee on Development (NGO-COD Thailand), bringing together 300 people from national civil society organisations (CSOs), political parties and grassroots activist communities at the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre (BACC).

With a majority of grassroots human rights defenders (200+), the room reflected a living map of Thailand’s peoples’ movement, connecting a plurality and diversity in justice movements from across the country, covering issues on land and resources, housing and labour, peace and gender, health and renewable energy, as well as anti-racist struggles for the rights of migrant workers. Activists from Southern border provinces affected by conflict were also present.

All participants collectively discussed democratic participation, the constitutional referendum, and protection of civic space. As part of the process, participants articulated shared structural policy demands addressed to ten political parties, reaffirming that human rights are unconditional obligations of the state and must be reflected in constitutional reform, laws, and enforceable mechanisms.

The networks and organisations represented included (among others):

- Assembly of the Poor Network

- Network of People who own Mineral Resources

- Patani People’s Activist Network

- Community Women Human Rights Defenders Collective of Thailand

- Eastern Thailand NGO Network

- EMPOWER Foundation / Sex Workers’ Network

- Thailand Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS

- Rak Ranong–Chumphon Network (Land Bridge/SEC opposition)

- Pha-Thung Sarong Warriors Network (Chana industrial estate impacts)

- Four Regions Slum Network

- Rim Rang Council Network and Khon Kaen Provincial Homeless Network

- Thai Overseas Workers Union

- People’s Network Against Discrimination (MOVDI)

Why did democratic participation come up as a central theme in the conference?

Democratic participation became central for three connected reasons.

Firstly, it links directly to the constitutional moment. Many networks including the Community Women Human Rights Defenders Collective of Thailand insisted that a new constitution must be people-drafted, grounded in human rights, and designed to prevent state officials from using security, bureaucracy, and courts to silence public voice.

Secondly, because the conference wasn’t ‘consultation theatre’. It was a direct assertion of power by people who live with the consequences of policy: farmers locked into debt, communities harmed by mining, slum communities pushed out of cities, Patani communities living through decades of conflict, sex workers criminalised by law, people living with HIV facing discrimination, and women human rights defenders confronting threats and SLAPPs, among other pressing concerns.

And finally, because people are demanding decision-making power, not sympathy. This was about shifting from being treated as “beneficiaries” to being recognised as rights-holders and political actors who shape the country’s direction. The issues are structural so participation is not optional, it’s the remedy. Land tenure, mining, mega-projects, welfare, care work as work, militarisation, or discrimination, are not technical problems. These are political problems that must be addressed with the common good in mind.

Ultimately, democratic participation wasn’t a ‘theme’. It was the method, the demand, and the political line running through every proposal.

What facilitation approach did PI Thailand use in the event?

PI Thailand supported the NGO-COD to design a space that felt serious, safe, and energising. The PI approach was a feminist and movement driven facilitation that helped networks do three things: connect, sharpen, and act.

The morning was dedicated to collective learning and cross-movement weaving. We used a participatory, ‘fun-but-political’ methodology that helped each network share lived realities and identify the structural causes, allowing participants to recognise the interconnectivity across struggles (land ↔ housing ↔ welfare ↔ militarisation ↔ discrimination), and translate this into clear policy recommendations that could travel beyond the room.

For the afternoon, we transformed the room into a rehearsal space for the theatre of power and politics. PI facilitated HRDs and networks to consolidate their demands into sharp messages, to practice speaking with confidence and collective backing, and to enter dialogue with political parties not as petitioners, but as people setting the terms for accountability.

Protection, participation and dignity underlied it all. The process was designed so defenders and directly affected communities could speak as leaders with safety, collective care, and political clarity. The political parties were placed where they belong: answering to the people.