What is a public policy for the protection of the right to defend human rights?

A “public policy for protection of the right to defend human rights” is a set of institutional laws, mechanisms and actions that develop and coordinate concrete actions for State authorities to promote and protect individuals and groups who engage in human rights defense. The core principle of such public policy should be to consider Human Rights Defenders (HRDs) not just as “objects of protection”, but as “subjects of rights”.

Taking this premise as a basis implies that the main goal of a public policy should not be as narrow as to react against attacks and aggressions, but a broader one: to enable the free exercise of the right of every person to defend human rights, and to guarantee the right of everyone to be a human rights defender.

A public policy should thus aim at addressing the root-causes of violence against HRDs (preventing stigmatisation, creating an enabling environment, provide space enough for their activities, eliminate barriers) and not just the “tip of the iceberg” (reacting when attacks occur).

The set of institutional laws, mechanisms and actions forming a public policy should be based on the UN Declaration on HRDs, and incorporate the standards provided by the Reports, Resolutions and Declarations issued by the various international and regional bodies.

Why are public policies necessary for the protection of human rights defenders?

Although society as a whole plays a role in the construction of an enabling environment for human rights defence, States and their public authorities are those ultimately responsible for their protection and, more broadly, for guaranteeing the exercise of the right to defend human rights. A wide range of standards and recommendations made by international and regional human rights bodies points out at the obligation of States to adopt measures that guarantee that defenders can defend rights without fear from threats and attacks.

Those recommendations should be applied in a comprehensive way, so to build a safe environment for human rights defence. This starts with the creation of a legal framework and a set of public policies that coordinate actions across institutions, both for prevention of attacks and for quick reaction when these occur.

In practice, we observe though that States have not adopted comprehensive policies to address existing violence against human rights defenders. Only a few of them have put in place some protection mechanisms and they focus on ad-hoc security measures, such as panic buttons, bullet-proof vests, CCTV cameras, sometimes bodyguards and other. Actually, these measures fail to reduce violence against defenders, since they do not address the underlying root causes of the structural violence that put HRDs at risk.

The problem of violence against HRDs is a complex issue that cannot be solved through protection mechanisms that work in isolation from other government and state institutions. It needs to be tackled from different angles, coordinating action from different institutional actors. This complexity is best approached from a public policy perspective.

Protection mechanisms and measures should be part of broader public policies that coordinate laws, instruments and actions aimed at guaranteeing the right to defend human rights.

All public policies on protection of Human Rights Defenders need to include a broad and comprehensive understanding of the Declaration on the Right and Responsibility of Individuals, Groups and Organs of Society to Promote and Protect Universally Recognized Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (commonly named UN Declaration on HRDs). They should also further take into account and implement the growing set of standards from later UN resolutions and declarations, as well as from regional bodies.

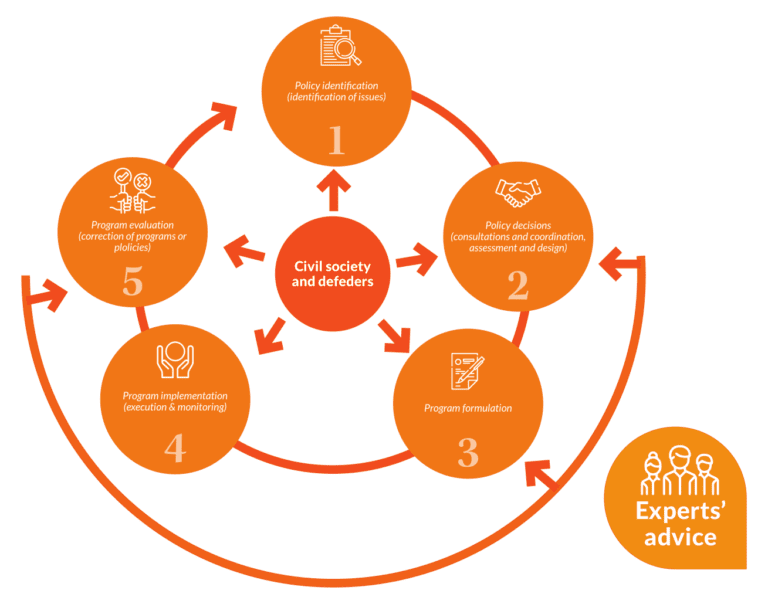

Acting as roadmaps towards a better environment for HRDs, public policies require careful planning, implementation, regular evaluation and, when necessary, corrections. Technical procedures and expertise are key to offset political influence within the policy-making process – especially if they come from a wide pool, including not only the government, but also both human rights defenders and civil society members at the national and, in some cases, at international level.

The role of states in protecting human rights defenders

States have the obligation to protect human rights. This includes the obligation to protect the right to defend human rights and the particular rights it encompasses (such as freedom of expression, right of assembly, right to demonstrate, right of association, right to disseminate information, amongst others).

States have the obligation to:

- Ensure a safe environment for the exercise of the right to defend human rights, by adopting legislative, administrative and other measures that create a conducive legal framework for the free exercise of rights.

- Provide an effective response that prevents and prosecutes attacks. States should do so by adopting the necessary measures and mechanisms to guarantee the protection of all people that, while exercising their legitimate right to defend rights, are victim of threats, retaliations or discriminations – regardless of whether these attacks come from State actors or private individuals.

According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, States’ action regarding HRDs includes:

- to provide the necessary means for those who defend human rights to freely carry out their activities

- to protect them when they are subject to threats, in order to avoid attempts on their lives and integrity

- to refrain from imposing obstacles to the realization of their work

- seriously and effectively investigate violations committed against them

Consequently, the adoption of laws for the protection of HRDs might be one – but not the only – response of state authorities to the threats and risks faced by HRDs. Indeed, responses of this kind may be converted into dead letters if the protection programme, the resources required to implement it and the criteria used to evaluate its effectiveness are not clearly established, and if space is not made available at all stages for the participation of civil society.

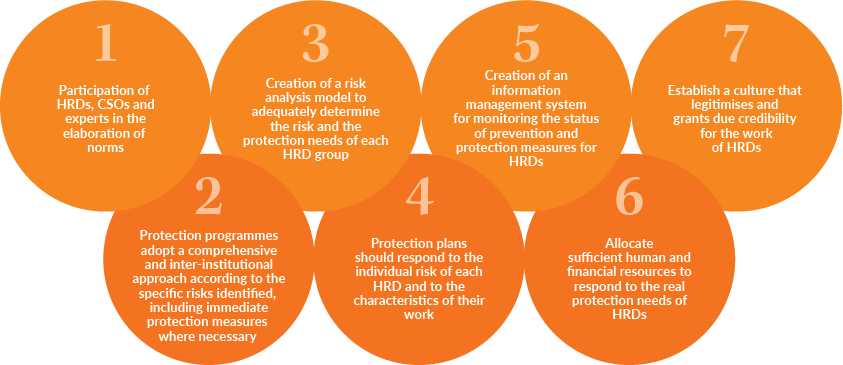

The obligation of states to protect HRDs has been recognised both by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and in the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights (IACtHR). Based on PI expert advice in two emblematic cases against the states of Honduras and Guatemala, respectively, the IACtHR rulings provided guidance on at least seven minimum requirements for HRD protection public policies:

Key elements to build a comprehensive protection public policy

- A clearly threatening context;

- The existence of networks (either formal or informal, involving HRDs organisations);

- HRDs’ access to policymakers, and the degree of openness by the government.

- Building political will;

- Ensuring participation of HRDs and civil society actors;

- Defining the problem from a structural perspective;

- Maintaining a broad and inclusive definition of HRDs;

- Including analysis of the perpetrator.

A public policy to protect the right to defend human rights should include:

- Prevention of:

- Attacks on the lives and physical integrity of HRDs

- Acts of aggression committed against HRDs by non-state actors (private sector, organised crime)

- Violations of HRDs’ rights to assembly and association, and freedom of expression and movement

- Defamation and stigmatisation of HRDs and their collectives

- Arbitrary detention and criminalisation of HRDs

- Monitoring and analysis of:

- Documenting violations and abuse of HRDs, identifying groups at particular risk

- Additional risks faced by HRDs because of their gender

- Active discrimination against sectors of the population and in particular linked to their human rights defence activity

- Elimination of:

- Restrictive laws that criminalise and hamper the right to defend human rights (peaceful assembly, freedom of expression, access to information and dissemination of information

- Restrictive NGO laws that hamper access to funding and put administrative and financial restrictions

- Barriers to accessing existing public policies (gender, language, geographical isolation)

- Evaluation and coordination:

- Evaluate the real results of the measures and actions adopted through the public policy

- Adopt effective and transparent ways of evaluating the level of risk faced by HRDs

- Ensure coordination amongst institutions, particularly strengthening the role of National Human Rights Institutions